What exactly is a neighborhood?

I frequently get asked, “What exactly is a neighborhood?” The question has more options than you might think.

For some, neighborhoods are defined by the city itself as a way to organize residents and others have historical names or based on a nearby school or park. Some neighborhoods have more residents than my entire hometown of Ash Grove, so does that make all of Ash Grove just one neighborhood?

Many communities have subdivisions with names alongside subdivisions that also have Homeowners Associations (HOAs) for governance. In many towns, no effort has been made to define or identify neighborhoods or associations.

This we know for sure: neighborhoods are specific geographies. Legal definitions may be suitable sometimes, but practical ones are better.

DEFINITION ONE

In her book on neighborhoods, Emily Talen, a professor at the University of Chicago, offers a clear definition.

A good neighborhood will have eight

qualities:

1. It has a

name.

2. Residents

know where it is, what it is, and whether they belong to it.

3. It has

at least one place that serves as its center.

4. It has a

generally agreed-upon spatial extent.

5. It has

everyday facilities and services, although it is not self-contained.

6. It has

internal and external connectivity.

7. It has

diversity or is open to its enabling.

8. It has a

means of representation, a means by which residents can be involved in its

affairs, and an ability to speak with a collective voice.

DEFINITION TWO

My friends at the Hopeful Neighborhood Project define a neighborhood as a residential area where you can walk from one boundary to another in 30 minutes.

This idea of walkability is practical and especially useful in more urban settings. But not every 30 minute walk will cover an area that is connected, has representation, or even has a center.

Some communities have decided to use City Council zones to place boundaries on neighborhoods. This makes sense for representation in government, it does not always make sense for social connection or getting neighbors to work together.

Depending on the are of the area or community, I think it makes more sense to consider the history of surrounding residential homes to create association boundaries.

DEFINITION THREE

Seth Kaplan, author of "Fragile Neigborhoods," has this to say on the topic: "A neighborhood should reflect what residents themselves view as their neighborhood and its boundaries—a place where there is some sense of collective identity and mutual responsibility, if not a shared feeling of common community (a much higher bar)."

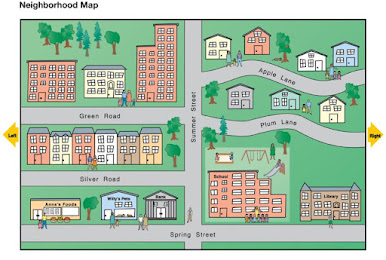

According to Kaplan, in an urban setting, a neighborhood should ideally correspond to the catchment area of a primary school, include a commercial center that can provide everyday facilities and services, and contain physical assets and institutions that promote bonding and bridging social capital (e.g., parks, libraries, public transit, and community organizations).

In a more rural setting, a neighborhood may mean the whole county, with the county seat being the main point of congregation.

If businesses have a robust way to cooperate to advance the common good—such as through a community investment district—the neighborhood can more easily build up assets and acquire outside resources for improvements.

If the place has a brand name (e.g., Harlem) that can be promoted, these goals will be easier to achieve.

CONCLUSION

The average

homeowner lives in a particular place for 13.2 years, three times longer than

the average employee spends in a job. Our neighborhoods determine what people

and institutions we interact with can determine the skills we develop, our

access to opportunity, our models and mentors, and the kind of relationship we have with the rest of society.

Yet, too

often, our society has downplayed the importance of the physical neighborhood.

This reluctance is another example of our unwillingness to recognize

relationships, commitments, and the places that nurture them as essential to

human flourishing.

For too long, we have downplayed the

importance of neighborhoods while also using that term to reference any dump of

housing put up.

For many of

us, geography is all we have in common. But we should not underestimate the

strength of the bonds shared geography can create between people who might

otherwise feel little connection to each other and be on opposite sides of

class, race, or political divides.

Whether urban, suburban, or rural, neighborhoods have traditionally anchored our relationships and provided the sense of security, belonging, and meaning everyone needs to thrive. Only in the past 20-30 years has that dramatically changed, and that is not good!

###

Does this article make you interested in taking the Engaged Neighbor pledge? Five categories and 20 principles to guide you toward becoming an engaged neighbor. Sign the pledge online at http://engagedneighbor.com.

Contact the blog author, David L. Burton at dburton541@yahoo.com.

Comments

Post a Comment